|

1 Comment

(Reflections at the opening of the Platform for Ethics and Politics of Technology dd November 13th 2020)

Let me first congratulate the initiators at the University of Amsterdam with this important new Platform for the Ethics and Politics of Technology! A wonderful initiative indeed. I am happy to be given the opportunity to pose a question to this Platform at its inauguration. Let me start with a kind of reflection: If there is one thing we came to realize over the past year, then it must be the realization that we live in a tremendous complex world and that we are surrounded by complex systems: from a biological cell, made of thousands of different molecules that seamlessly work together, to our society, a collection of seven billion individuals that try to live together, to the millions of computer systems that should work together. All these complex systems display endless signatures of emerging order, disorder, self- organization and self-annihilation. Understanding, quantifying and handling this complexity is without any doubt one of the biggest scientific adventures of our time! Now this realization that everything is connected to everything is not new, from Lao Tse (in Tao Te Ching) to Benedictus de Spinoza (in Ethica) philosophers have pondered on this inter connectivity and asked themselves questions on how to act in that web of interwoven causes and effects. (Benedict de Spinoza (1665): ‘Every part of Nature agrees with the whole and is associated with all other parts’.) But then in the 20th century something special happened with the invention of the internet (and the internet of things) resulting in the ubiquitous presence of information. Suddenly the ties became more tight, the links more abundant and with an unprecedented speed we all added physical, social, economic, behavioral, emotional information into that treasure trove we now call the internet. About the same time my field of research -complexity science- emerged in a tiny corner of the world in New Mexico where the Santa Fe Institute was pulled together by Nobel laureates, to quantitatively study these complex adaptive systems. This research is done by combining Baconian inductivism (data science, now called AI/ML) with Popperian reductionism (models and experiments) using computer simulations. This type of research into cause and effect across interwoven processes is making massive progress. Some of which is – I am happy to say- also coming from the Institute of Advanced Study here at the University of Amsterdam 12. The consequence of all this is that, more than ever, we are able to integrate data and models and concepts from all disciplines into integrated systems that can be used to answer ‘what-if’ questions and to explore through numerical simulation the consequences of physical, infrastructural but also social and political interventions in the systems that build up our society. Think of behavioral interventions in our healthcare system, our economy, our way of handling the energy transition or the climate crisis. The result is a kind of policy by simulation. Which brings me to my research questions for PEPT: Given this reflection I am pretty sure that we might soon know how to nudge people and their behavior in a way that will improve our quality of life, that might save our biodiversity, spare our scarce resources, feed the hungry, give migrants a home and build a healthy resilient society. We have come already a long way, but we now have the technology and the opportunity to move much faster and much more efficient by exploiting this interdisciplinary knowledge. BUT, a very big but… nudging people’s behavior can be a great thing from a collective point of view but completely unethical from an individual perspective. So how to resolve this ethical disparity? And … if this nudging can happen then it will happen… that in return begs the question; Should the politics be an active agent in that process or be passive and just provide guidelines? I sincerely hope that the PEPT initiative will consider to put these questions on their to do list, not tomorrow but now, as the need is already here and the time to act is now!

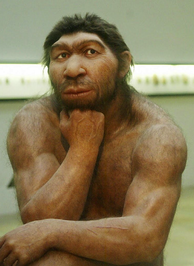

No doubt Charles R. Darwin was right when he discovered 'the survival of the fittest', even Sharon Moalem has an excellent point when he speaks about 'the survival of the sickest' [1], but what is really shocking is what I recently discovered: 'The Survival of the Stupidest'. Here is a way to look at it: Our brains are constantly integrating information about the world around us. That requires neuronal activity that can not be used at the same time to to do other things, such as actually think. Multi tasking is a myth debunked time and again [2]. Deep thinking about truly complex problems require total concentration. There is no room for assessing ones environment for imminent threats. So if in the early days of the hominoids, at the dawn of homo sapiens, our species would have been engaged in deep thinking the result would be clear: the individual would simply not survive long enough to reproduce. Consequently there will be no 'deep thought' genes to be inherited [3]. ... and then there is a Sabre-Tooth Cat lurking in the back ... This selective process continues to date: try thinking very hard about a complex problem while crossing the road... If you start young enough doing so you can rest assured that your genes will stay unique and will not be transferred into the pool of humanity. And because of the pre-selection that already happened over the past couple of hundred thousand years, there can only be one conclusion: We are stupid. [1] Sharon Moalem, 'Survival of the Sickest', HarperCollins Publishers, 2007. [2] The Myth of Multi Tasking: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/creativity-without-borders/201405/the-myth-multitasking [3] Of course it is still an open debate whether 'deep thought' genes actually exist, or whether it comes about from epigenetic selection or is just adaptation or nurturing... Astronomers of the Maya civilization and astronomers of the Babylonian civilization were brilliant in predicting astronomical events. For instance, from meticulous observations of the Sun, Moon, Venus and Jupiter they were able to predict with astonishing accuracy the 584-day cycle of Venus or the details of the celestial track of Jupiter [1]. Yet they had no clue about our heliocentric solar system, they believed that the earth was flat and they were completely ignorant of the real movement of stars and planets while being convinced that the sky was supported by four jaguars, each holding up a corner of the sky.

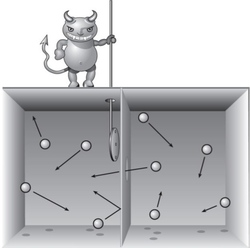

They were basically doing what is now called Big Data or Data Science, a very powerful way to uncover patterns in historical data. Unfortunately, data science on its own might introduce false interpretations of causality, like jaguars carrying the sky. What we need in addition to that are computational predictive models that use fundamental first principles and mechanisms that can track the system over time and allow for quantitative validation and provide pointers to novel experiments to falsify or confirm our interpretations. In other words, we need a merger of the 'inductivism' from Sir Francis Bacon (Big Data) and the 'deductivism' from Sir Carl Popper (first principle computational models) [2,3]. If we manage to turn a potential clash of these two titans of science into an integrated scientific paradigm, then the holy grail of the Scientific Method as a way 'to discover that Nature hasn’t misled you into thinking you know something you don’t actually know ' [4] will be one step closer. See also a lecture I presented in May 2017 at the Complexity Hub in Vienna: Here. [1] M. Ossendrijver, Science: Vol. 351, Issue 6272, pp. 482-484. (2016) [2] P.M.A. Sloot, P. Coveney and J. Dongarra: Journal of Computational Science Vol. 1 (2010) 3–4; [3] P.M.A. Sloot in 43 Visions for Complexity, Ed. S. Thurner, p65-66 World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. ISBN 978-981-3206-84-7, 2017 [4] Robert M. Pirsig, 'Zen in the art of motorcycle maintenance', 1974  I am trying to defy the second law of thermodynamics by acting as a demon gatekeeper and only allow the 'hot' papers to go for a review. With a bit of luck I can avoid chaos and create a scientific meaningful journal. That is not trivial, if I succeed I will frustrate many authors and be considered a real devil, if I fail I will contribute to the total paper pulp and add more casualties to the citation massacre... |

AuthorPeter Sloot Archives

February 2021

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed